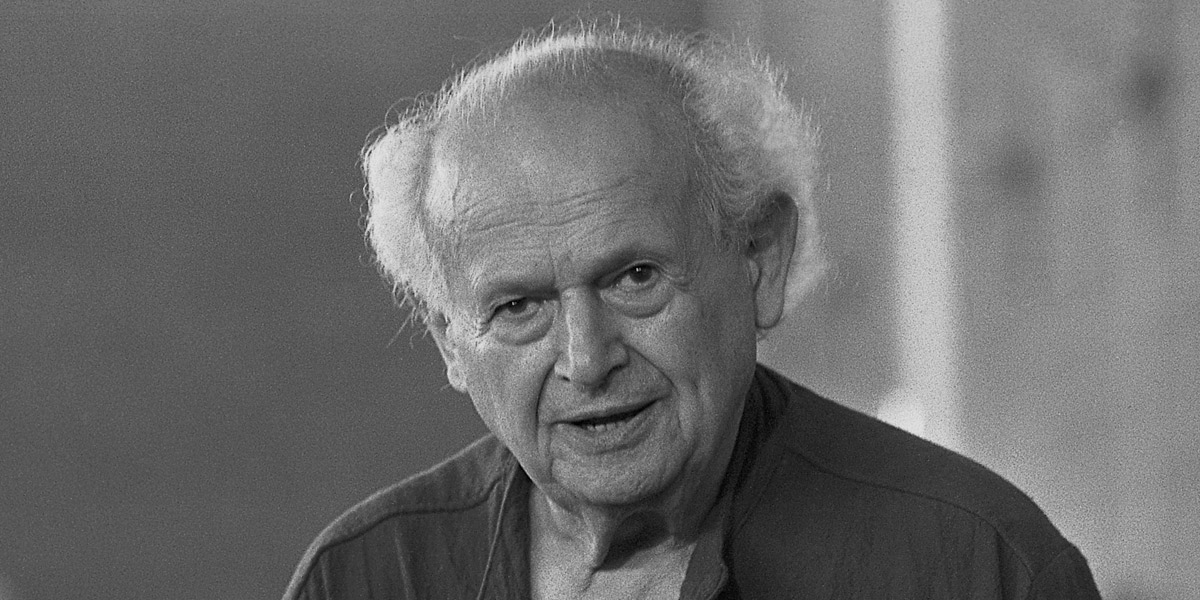

Moshé Feldenkrais

Feldenkrais’s scientific work was always drawn from life. He linked his physical knowledge, his understanding of neurophysiology, developmental psychology, biochemistry and behaviour research with insights from his own kinesic behaviour and his experience as a master of judo. From the 1950s right up until his death in Tel Aviv in 1984 he dedicated himself exclusively to practising and developing his method.

It is in the essence of every art form, that he who practises improves his abilities and his motor skills become increasingly differentiated and varied, right into old age.“ Feldenkrais suggests that „we should worry less about what we do but rather concern ourselves with the way we do something, whatever that might be. Because the way we do something is the sign of our individuality. Moshé FeldenkraisMoshé Feldenkrais teaching a workshop:

Now, we will see, as always, if something can be better. Then, there isn't any limit to the extent to which it can improve. It is only static things that are permanent. With a quality like intelligence, [or] where intelligence is involved, there isn't any limit. The person can do it so it improves. Then, literally throughout life, he, or she, will never find "a best way," that cannot be improved upon.Then, when he, or she, stops improving, it is a sign that it has become a routine and he no longer sees [or is aware of ] what he is doing. He is acting mechanically and that is why it is not improving; otherwise, there isn't any limit to development. As a person does better, the ability to feel becomes greater and the clarity, depth, and breadth of thought is increased. The complexity is also increased, so that he, or she, can always do better, much better.